It’s TIFF time, again, and I caught my first two (well, three really) films tonight. My first screening was a film about Haiti — TIFF seems to have one about every other year, and I always make a point of catching that screening.

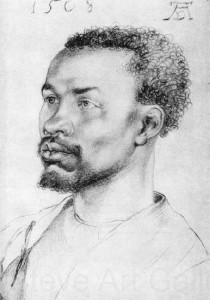

According to the programme, the film was meant to be preceded by another film called Peripeteia, but there was some screw up and we ended up seeing that one second. Peripeteia is a fairly avant-garde film, and I can’t say that I love avant-garde. It starts out with a title card informing us that the painter, Dürer, produced “Head of a Negro” in 1508, but that all information about the subject has been lost to “the winds of history.”

According to the programme, the film was meant to be preceded by another film called Peripeteia, but there was some screw up and we ended up seeing that one second. Peripeteia is a fairly avant-garde film, and I can’t say that I love avant-garde. It starts out with a title card informing us that the painter, Dürer, produced “Head of a Negro” in 1508, but that all information about the subject has been lost to “the winds of history.”

Cut to a black actor who looks vaguely similar to the sketch. He’s in sixteenth-century Europeean garb, walking through the fields of the dreariest British countryside. It looks Too Fucking Cold, and we can hear non-stop winds. He walks a bit. We cut to him in a different field. He stands dramatically. Cut to him near a lake.

We’re also informed that Dürer sketched a woman known as Katharina. Cut to an actress who looks like Katharina. For the length of the film, we see the two actors, almost always apart, walking through different fields, and sometimes near rivers, while we hear the winds blowing. They don’t speak. They don’t really interact with anything. It’s all Very Deep and Very Dramatic. It’s also interspersed with two types of still images: the first are old black and white photos of Africans looking stereotypically tribal. There’s scarification and grass skirts and bare breasts. The whole works. The second set to still images were close-ups of figures in paintings — both black-skinned and white-skinned figures. The artist wasn’t identified, but I guessed it correctly as Bosch. Because the images are in such extreme close-up, it’s hard to recognize the source paintings.

We’re also informed that Dürer sketched a woman known as Katharina. Cut to an actress who looks like Katharina. For the length of the film, we see the two actors, almost always apart, walking through different fields, and sometimes near rivers, while we hear the winds blowing. They don’t speak. They don’t really interact with anything. It’s all Very Deep and Very Dramatic. It’s also interspersed with two types of still images: the first are old black and white photos of Africans looking stereotypically tribal. There’s scarification and grass skirts and bare breasts. The whole works. The second set to still images were close-ups of figures in paintings — both black-skinned and white-skinned figures. The artist wasn’t identified, but I guessed it correctly as Bosch. Because the images are in such extreme close-up, it’s hard to recognize the source paintings.

I have no idea what the film was trying to say. Perhaps it was just trying to show us an uncommon subject: black folk in medieval Europe. But the reference to the notion of peripeteia suggests a deeper meaning that, I confess, is eluding me.

For my part, I was more interested in the main film: Three Kids (Twa Timoun). This film follows the lives of three young boys who live in Pòtoprens. The film starts on January 11th, 2010 — the day before the earthquake. After the earthquake, they’re living on the street, wandering from place to place. Sometimes they act like kids and spend time kicking something vaguely ball-like around in a poor approximation of soccer. Sometimes they’re stealing water from a water merchant, or stealing something that they can sell to buy some food.

The film is a bit rough. The pacing is slow. The acting is fairly uneven, and there are times when some non-linear story-telling seems to add some confusion about the overall plot. It’s also true that it’s hard to communicate certain evens — like, say, the earthquake — filmically without any budget to speak of. Eventually the kids move into an abandoned building, and the character’s backstories start playing a role. Vitaleme was abused by his uncle, and has a lot of anger. And some problems with pyromania. Mikenson’s sister died some time ago, and he ends up meeting a girl who reminds him of his sister. And that’s when Vitaleme’s issues takes the story to an overly-dramatic climax. In my opinion, it doesn’t really work.

On the plus side, there are some beautiful shots in it. There’s an amazing shot of Vitaleme in the ruins of the Cathédrale that’s absolutely striking. But it’s an imperfect film.

The Q&A afterward had what I thought was an important moment. One woman asked how true-to-life these boys’ situation was and wanted a good recommendation about charity to donate to. The director, Jonas D’Adesky, replied that the “environment” in Haiti wasn’t really conducive to the NGOs getting much accomplished. The next commenter — a member of the Haitian diaspora — was a bit critical of the film. He made two primary points: first, that many of the moments in the film seemed too divorced from reality. In truth, the kids could not have gotten away with some of the thefts you see in the film. Would not have been welcomed into some of the places they went to. His second point was that portraying post-earthquake Haiti as a buddy flick was doing the country a disservice. As was dissing Haiti’s “environment” in the answer to the previous question.

I don’t think he quite managed to make this point in these terms, but I think his general point was that foreign-authored narratives about Haiti carry a lot of weight — far more than the narratives created by Haitians — and that those narratives need to be responsible. D’Adesky seemed to brush off the complaint saying simply that such things weren’t his “purpose” — that he was just telling this story about these kids. D’Adesky’s response elicited a fair amount of approving applause, which disappointed me because I thought that the questioner’s point was quite valid. I caught up with him and chatted with him in the hall, briefly.